By Tom Wilson

An option pool is a key tool at a high growth startups disposal to attract and retain top talent. This post sets out some of the key concepts that founders should consider when thinking about granting options to employees.

What is an option?

Options are contracts that grant the right, but not the obligation to buy or sell an underlying asset at a set price on or before a certain date. In our case we’re focused on the right to buy a set number of shares at a specified price on or before a defined date. The price is often referred to as the “strike price” and refers to the price set on the date the options are granted. In successful startups, options can become very valuable as the fair value of the shares in the company increases significantly beyond the strike price.

Why do startups grant employees options?

There are a number of key reasons for startups to grant options to employees:

(1) Alignment of interests – options allow employees to share in the success of the startup (alongside its founders) and potentially provide an additional inventive for an employee.

(2) Economic / pay – options also provide a mechanism by which startups can fill the gap between what an employee could earn in the market and what a startup is able to pay. For example, an employee may be able to earn £100k working for a large tech company with an additional very small option package (or none at all) whereas a startup may not be able to match such a salary but is able to offer a potentially more generous options package.

(3) Retention – most option packages are on a vesting schedule and/or be subject to leaver provisions (all Seedcamp and other VC backed companies will include vesting in their ESOPs). Therefore, employees who receive options will be additionally incentivised (in positive situations) to stick around to gain the maximum benefit.

(4) Tax and governance – when considered in comparison to issuing shares to employees rather than options, options have the benefit of potentially being more favourable from a tax perspective (see below). Also if shares are issued the employee would become a shareholder in the startup and inherit certain rights (i.e. dividend, information, voting) that may not be appropriate.

How many options should the first employees get?

This is a common question that comes up regularly with the companies that I work with. There’s no magic formula and often the answer is the incredibly frustrating “it depends”. The process is often described as more art than science and it’s very difficult to point to an exact way of answering the question.

There’s some great posts out there going into more detail on the topic so I’m not going to dwell on this here but I’d recommend reading these to get an overview of methods to arrive at amounts for individual grants broken down by roles:

And these posts looking at the evolution of option pools over numerous rounds are worth checking out:

Option Pool sizing — by the Numbers.

A key point to note, that my colleague Carlos flags in his post, is the importance of being clear with what % the grant is in relation to. It’s important to highlight that the % is in relation to the current fully diluted cap table (at the date of the grant).

eShares have a great example of how they explain employee equity to new hires in their offer letter – in this, they clearly set out the scenarios and what such a grant could be worth to the employee. Buffer famously also include a full transparent breakdown of how they calculate option grants and the factors and variables they take into account — more on that here.

How do startups grant options?

Once the total pool size and breakdown has been determined the process needs to be properly documented. Getting the paperwork right is crucial to avoid complications down the line.

For UK companies, generally, the first thing required is to get an Employee Share Option Plan (ESOP) written up and approved by the startup and its board. Such a plan requires careful drafting and advice from a specialist tax adviser and/or lawyer. Most UK startups go down qualifying their ESOP under the Enterprise Management Incentive (EMI) route. The major benefit of this approach is that it potentially means there is no income tax payable by employees when exercising their options — only on the gains on an exit (where Capital Gains Tax (CGT) will be payable). This is a significant potential tax benefit for employees. Before any option grants are made it’s necessary to get a valuation of the startup done. Such a valuation for an EMI qualifying ESOP is different from that referred to at a funding round (where it’s set by third party investors (VCs, Angels etc.)) and in this case actually requires an application to be made to HMRC. Care needs to be taken with the application and advice should be sought from a specialist accountant to assist. Obtaining a low valuation for the purposes of pricing the options (strike price) is generally seen as preferable because it will maximise the potential gains and therefore the impact of the grant for the employee (as such it’s helpful for hiring purposes). The valuation will only be valid for a set period of time (~60 days or so) so it’s important to make the option grant shortly thereafter. It’s worth noting also that options granted under the EMI route only qualify if made to employees. Once all the paperwork has been approved, finalised and signed by startup and employees the option grants need to be filed with HMRC (within 3 months) to qualify for the tax advantage.

The market for options in Europe

Overall I don’t think there’s enough value given to startup options in Europe. Perhaps this is down to the risk tolerance of us Europeans and our tendency to favour a certain salary over equity. I’d like to see European startups be more aggressive with their option grants and spend more time educating employees as to the potential value that such option grants could present. It feels like there’s value being left on the table there. The US market appears to be ahead in this regard probably buoyed by the fact founders there can point to more success stories of startups scaling to exit. For any startup, one thing is for certain, talent is absolutely critical and therefore spending time devising a strategy around how options can be used to attract and retain world-class talent is time well spent!

— — —

It goes without saying that ESOPs are a complex area and advice should be sought from a qualified account and/or lawyer to ensure all the proper steps are taken. Also to note, the above is meant only as a quick summary and there are some other points to consider such as: eligibility criteria and a maximum amount that can be granted (the full criteria can be found here).

“Product” is a tricky notion in a startup, or any company new to the discipline. Who does it? What skills does it require? How do you know if you’re doing it right? It’s not like Marketing or Tech, which are (comparatively) well-understood, degree-backed disciplines with a large pool of talent at every rung of the ladder. Yet Product is just as critical to a startup, if not more so in the earliest stages, since if you don’t have a good Product, in most cases, none of the other stuff matters. We can all think of examples where a great idea just couldn’t get a very compelling Product developed, and it sort of whimpered out of business.

Everyone has an intuition of what “Product” means, even if most people have never worked in an organisation where there was a formal “Product” function. Its something to do with the “vision” of the business, and something to do with the actual software “design” that users interact with.

Product operates both at a Strategic (What do we do/build?) and Tactical (How do we build/run it?) level, with the former being more important in the early stages of a company’s life, and at that stage largely overlapping with “business strategy”. For this reason, typically the founder(s) are responsible for Product for at least the first few years, though I have been seeing our startups hire Product specialists earlier and earlier.

Whether it’s you the founder, a new product manager, or a whole team, here are some of the things you should expect your Product function to do a great job of delivering;

How does it feel when it’s going well? Everyone in the company knows what you are working on, in what order. The things you work on align well with your business strategy. Leaders in the business feel heard and get their priorities addressed.

How do you get it? You’ve got a long-term roadmap laid out in general (not feature-level) terms. You’ve got a short-term (90 day) development roadmap locked in with only the highest priority metrics in focus. There’s a high-bar for any changes to this, meaning crazy new ideas have to be really amazing to get into the development queue, and most ideas simply get chucked into the “opportunity cloud” to be revisited later.

How does it feel when it’s going well? You engage your users in discussion regularly and have a continued sense of their feedback, what they want, what they like/dislike. You also know what they are doing on your product and how that changes week on week. Both of these feed religiously into your planning process. Someone inside your business is really championing the needs of the User above all else.

How do you get it? You engage several different qualitative types of User Research, regularly, and summaries of these are distributed across the organisation. Perhaps a Customer Council? You have a culture of Validation before burning developer time on features. Analytics features prominently in your weekly meetings.

How does it feel when it’s going well? Product acts as a bridge between most internal teams, giving them all a sense of what’s going on and how they can impact it. Developers are happy with how clear their requirements are written. Everyone in delivery knows *why* they are working on each thing. Product performance is part of day-to-day vocabulary for everyone.

How do you get it? Product regularly updates the company on performance of recently launched features and progress toward goals. There is a dashboard, maybe even a Product Council? Product runs a well understood process for getting something from idea to delivery. Developers accept only clearly defined work.

So, if you feel like Prioritisation, Insight, and Clarity are solid in your startup, then you’re on the right track and you should congratulate whoever is performing the Product function. If it feels like you could use an upgrade in some or all of them, I’d be happy to recommend some of the wonderful resources out there, or talk with you about how to get you what you need (@twescoatt). More of my Seedcamp writing is here https://seedcamp.com/eir-product-articles/

Seedcamp Partner, Carlos Espinal, has written this piece focusing on how to show growth and traction for early-stage startups looking for investment, with key contributions from our Experts in Residence Scott Sage and Keith Wallington, and Jeff Lynn, CEO of Seedrs.

As an early-stage startup trying to fundraise, you’ll likely have to tell a version of your company’s story that demonstrates high likelihood of growth to attract an investor. Which are the stories that are most commonly used during the early stages of a business, and which ones later on?

In this post, we’ll cover the various forms of ‘validation & traction’ that you can potentially leverage in conversations with potential future investors as well as to create internal benchmarks for you and your team.

If we look back at this topic as a form of storytelling, below are the ’stories’ I hear the most (alone or multiple at once):

In previous blog posts, I’ve covered what makes an amazing team and how investors evaluate a team, what Tier an investor is in and how other investors might judge who is in your round. In this one, I want to focus on 4 and 5 of the list above. Basically, understanding when you have any kind of traction and what constitutes ‘impressive’ for the average investor.

One way of trying to benchmark what is ‘impressive’ is by looking at some companies that are generally considered to have done extremely well. In this Quora post, we can see a few of the companies often referred to as ‘impressive’:

Weekly Revenue Growth

However, as impressive as they are, these numbers don’t show the entire story. They hide various operational and industry dynamics that are only possible in the sectors in which those companies operate. For example, the cost of acquisition and the sales cycle for each of these businesses might be drastically different than yours. Looking at these figures as a 1:1 to what you have to achieve might create an insecurity complex and frustrating unit economics. Effectively, you can’t compare oranges with apples. They’re impressive for sure, but are they applicable to your company and is it realistic for you to sustain those kinds of numbers in the long term?

Whilst the above point might seem self-evident for extreme cases, I’m always surprised by what I hear some founders receive as feedback from investors when being compared to idealized growth cases.

Let’s kick things off with the easiest form of growth to talk about, user-growth in any kind of network effect business where monetization is not the immediate short-term goal. The most typical example will be social networks.

These kinds of companies are the ones that are the most referenced to when looking for ridiculous growth rates. Facebook and Twitter in their early days are good examples. However, before we get into what kind of week-on-week growth is impressive, let’s tackle one very big point that makes any growth meaningful.

If the business’s successful growth allows it to have lock-in effect, then a non-monetized growth strategy early-on makes sense as a way to monopolize the customer-base and once locked-in, monetization strategies can be considered without fearing user-growth-rate loss and churn to competitors and/or substitutes.

Not all businesses that embark on a non-monetized high user-growth rate strategy truly have lock-in capabilities so it is not unusual to have these be the ones most investors are less interested in. If there is any risk that you might fall into this category, start thinking about what could make your user-growth rate create a lock-in that no competitor could make you lose.

For these kinds of businesses where user growth rates are what is being used as a proxy for future revenue, a 6-10% week-on-week growth rate will be considered as impressive. Above 10% week-on-week would be considered as boss-level growth, as can be seen from Facebook or other companies mentioned in the Quora post above. Only a few companies frequently achieve these levels. Other impressive growth rates from companies falling into this category can be seen here.

Once a company decides it needs to be charging early-on because its product doesn’t have a network effect built-in (or where there are plenty of substitutes in their market), one can expect the company to be measured by a different set of growth rate standards. Although there are always exceptions, once money is involved, things get more complicated.

There are several factors that can generate a different set of growth rates, with the main ones being:

Sales cycles can vary greatly from business-to-business and can serve as a proxy for sales growth until you actually materialize sales. If you want a quick brief on sales cycles, this link will walk you through the basics.

Comparing growth rates of monetized companies becomes complicated because not all of them have the same sales cycles. We’re back to our orange to apple comparison dilemma. Some might have a heftier cost of customer acquisition but can sell immediately (such as software download), while others might require a subscription once someone deems the relationship with the service worthwhile (such as dating sites) but might be able to leverage virality effects intrinsic to their sector or customers’ needs/desires to lower their cost of acquisition. Life isn’t fair, but let’s try and see how we can compare businesses in these categories.

Let’s first start by looking at companies that have a long sales cycle. These companies might have interactions with their customers via newsletters, social media, click-throughs etc. but can have frustratingly low month-on-month growth rates on conversion. For those, a good starting point as a proxy for growth is to have engaging discussions really early on about the value you bring to your customers so you can use it as a proxy to the actual (and hopefully, eventual) conversion point. Try and find correlations between behavior and interactions with your product as a precursor to conversion between marketing initiatives (content marketing reads, etc.). This isn’t easy or pretty, but having nothing to speak about on why your early customer might care is likely unacceptable. This also helps to think about what kind of ‘features’ you can build into your product that can signal the intent of conversion in the future. For example, does adding things into a wish list you’ve created for customers increase conversion once key dates in the year come around (holidays or birthday).

As a software company, you should not get caught in the sales funnel trap. Too many startups equate growth to how many deal leads are being added to the sales funnel every week. Adding X% new business to your pipeline every week is great, but if the output — closed deals — is close to nil and not growing, you have a serious problem. If you and your team are able to convert your top of the funnel demand into an efficient sales process and close deals, well done. But if you’re like most startups, you will have inexperienced people adding every possible deal lead in the world into the sales pipeline without knowing 1) how to qualify those deals or 2) whether they even fit what a typical buyer looks like.

So, how should we think about traction from the standpoint of a software startup and their sales cycle? One important note to make is that the range of pricing varies greatly. A startup selling $100k enterprise deals will have a longer and more complicated sales cycle than a startup selling a $5k deal that may not require the board’s or your CFO’s sign-off. Investors want to see consistency in your sales execution. If you were able to close nine deals in the first quarter of focusing on sales, then they will want to see at least nine deals in the next quarter. The more deals your team closes, the better they get at qualifying opportunities, pushing the sale through, and understanding where various customers receive the most value from your product. Once you have a good idea of what your sales cycle looks like, then you should be able to shorten the cycle and in theory, close more deals faster with the same team.

At a high level for SaaS businesses, investors want to see an absolute minimum of 100% growth year-over-year. Assuming your sales and marketing team and costs stay the same from one year to the next, investors will expect you to retain a very high proportion of customers from the first year (let’s assume for simplicity you’re able to keep 100% of the revenue from year one’s customers by retaining 90% and up-sell another 10%). Then with the same team, you should be able to acquire the same number of customers with roughly the same size of contracts. So Y1’s recurring bookings + Y2’s new bookings = 2x Y1’s first year’s bookings.

Aside from Sales Cycles, there are other limitations that can create an artificial restriction on growth rates in early-stage companies, which make it unfair to compare companies like for like. Two examples include marketplace supply and demand balance, and operational limitations, which when optimized, lead to increased demand.

Various successful marketplaces have used a number of strategies to capture a market and grow, but all share a common pattern, which was to start from the supply.

Shutterstock, Founded 2003

Airbnb, Founded 2008

Etsy, Founded 2005

Quibb, Founded 2013

Key Lessons:

KPIs:

What investors look for in online marketplace businesses: growth metrics

Supply

Demand

Summary Table for how to think of where your company’s economic opportunities are

So, we’ve covered quite a bit of ground on user growth rates, sales cycles, marketplaces and the like, but how about for businesses where there might need to be some stockpiling of inventory first before going out to the market, or perhaps R&D and progress therein, before being able to announce/launch a product, or how about ones that are just getting better and better in their internal processes and waiting for the next inflection point in demand to really scale up after a fund raise?

For now, let’s focus on the optimization of production costs that are already existing in order to better demonstrate your company’s growth in preparation for a fundraising.

Optimizing production costs leads to unlocking the ability to service more customers and, therefore, to grow faster. Until fully optimized, you will be limited not by user interest, but rather by operational limitations. Week-on-week or month-on-month growth could, therefore, be pegged to operational improvements.

A number of operational blockades will need to be overcome throughout the customer journey:

Can start manually going through a human collection of leads such as contact details etc. and is appropriate for early-stage customer validation. The process must be automated or other lead sources secured to ensure marketing can deliver a growing volume of appropriate leads into the customer acquisition funnel.

Might be limited by the number of meetings each sales person can schedule and attend in a week/month- solution: study the sales funnel and automate where you can, improve use of CRM, evolve marketing lead qualifications and nurturing processes to deliver better-qualified leads to sales such that the customer is more progressed towards a purchase by the time they are handed to sales. Adding more sales people without optimizing these other pieces will likely see CAC not improving as the business grows

Manually onboarding and supporting customers is ok in early customer validation phase but must be automated to the maximum appropriate degree without destroying customer experience to avoid a bottleneck. Often an automated onboarding and support experience (with good monitoring, alerting and access to help) can improve customer experience as they can work at their own pace and not need to fit into a schedule

Process innovation by reducing issues internally and unlocking a new rate of growth. Marketplace growth requires balanced growth and should result in week-on-week growth.

In conclusion, there are many variables that can be used to determine a company’s growth and traction ‘by proxy’. In a recent chat with Jeff Lynn, founder of Seedrs, he said “the appropriate unit of time to measure a business’s growth varies from company to company. One of the things we’ve found with Seedrs is that month-on-month growth rates aren’t particularly helpful because we’re too spiky in terms of monthly transaction levels. When we look at month-on-month, one month we’re over the moon because we’ve grown 200% over the previous month, and then the next month we’re in despair because we’ve shrunk by 50%. We’ve now moved to measuring everything on a quarter-by-quarter basis — even that isn’t perfect, and our real cadence is more like six months, but we’ve had to balance that against the need to iterate and adapt quickly enough (although in our Series A fundraising materials, we should everything on a six-monthly basis, and it worked just fine).”

Hopefully, this post has given you a new way of looking at some potential ways for you to start tracking growth in your company to create a more compelling case for future investors.

To stay updated on the latest Seedcamp news and resources, subscribe to our Newsletter, and follow us on Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn.

This article was written by Taylor Wescoatt, one of Seedcamp’s Experts-in-Residence. Follow Taylor on Twitter @twescoatt.

This article was written by Taylor Wescoatt, one of Seedcamp’s Experts-in-Residence. Follow Taylor on Twitter @twescoatt.

This title isn’t entirely accurate I have to admit. It should be ‘Validate or Die Slowly!’. If you’re reading this, you’ve read The Lean Startup and other best practice, and you know that validating your ideas is critical to success. It is also the quickest way to figure out if you’re off track, so you can re-evaluate your options.

At Seedcamp, we work with lots of startups at a very early stage, so validation is super important and we do it a lot. It’s hard though, for a good reason. Customer Validation research is about systematically challenging your own beliefs. As a founder, our sense of self-worth is often woven in with our startup idea, so forcing ourselves to question that is painful. Until you get used to it, then it’s fun!

There is a huge amount of best practice and industry built up around validation techniques, and you can spend many thousands of pounds hiring people to help, but how do you do it yourself on the cheap? Before we dive in, let me make a few suggestions;

Here are the techniques I recommend;

Needs Analysis

Product Analysis

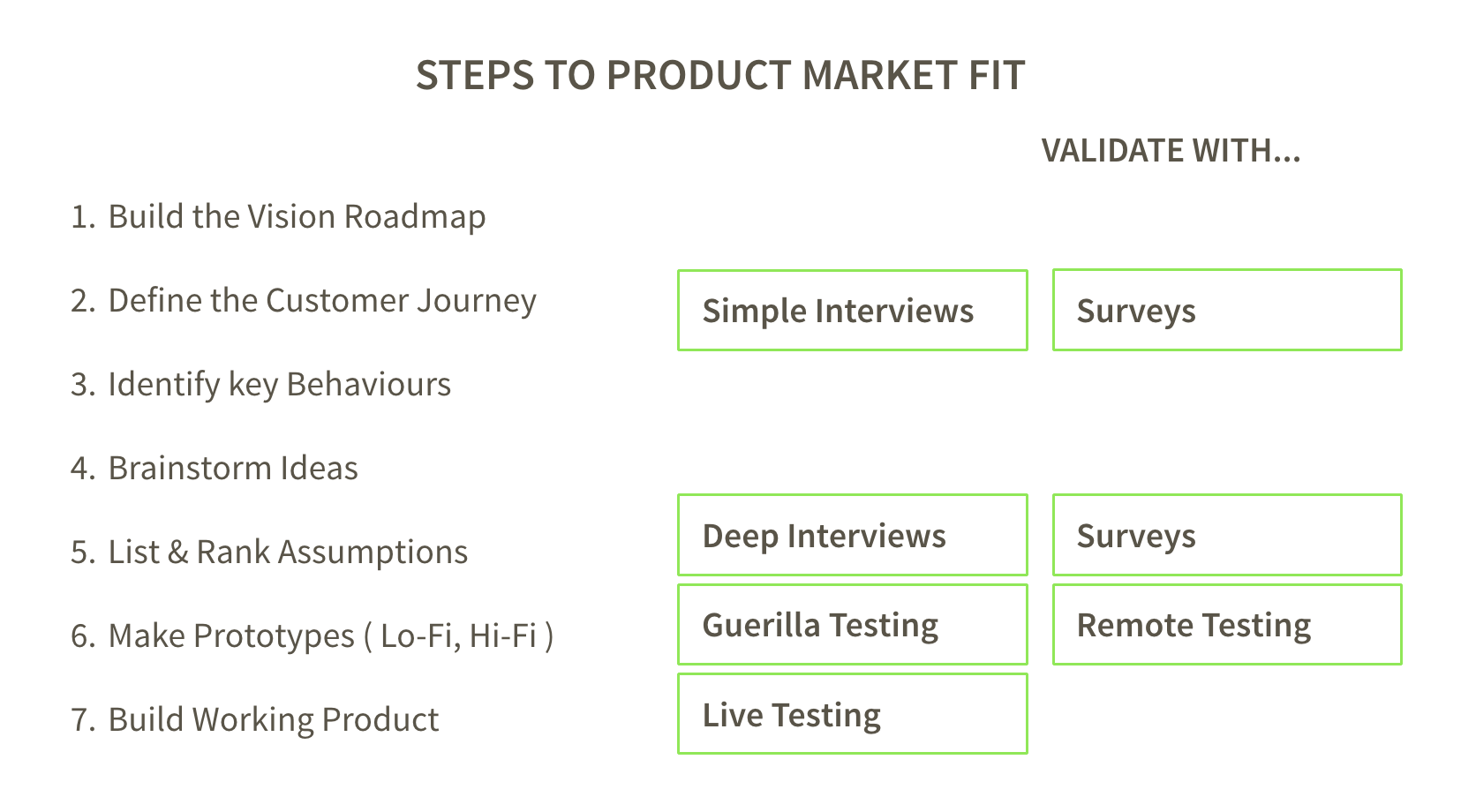

Putting it all together, here are some places where each type of testing can be helpful in the drive towards Product Market Fit;

A couple of extra things to consider;

Building validation into your process is the way to go. At first, it may seem laborious, but you’ll be thankful that what you learn will have saved you a lot of time, you’ll be happier that what you build will get used, and you’ll have a stronger culture of caring about the customer within your team.

For a list of all my articles: https://seedcamp.com/eir-product-articles/

This article was written by Taylor Wescoatt, one of Seedcamp’s Experts-in-Residence. Follow Taylor on Twitter @twescoatt.

Probably the most powerful tool for early-stage Product thinking is the Customer Journey. Literally, every step your individual Customer must go through in order to create value for your business. By capturing, developing, and working with this framework, you will;

A good Customer Journey is an ordered list of actions that your Customer largely must follow in order to achieve a state of real value (for the Customer). If you’ve already read about the Vision Roadmap, you’ll be familiar with this as “The Proposition”. The list starts often with a need (felt some pain, frustration) which leads to awareness, trial, experience, and then finally your customer’s real value state, habitual use, re-purchase, or referral, for example. Here are a few examples;

The first surprise most startups have in doing this is that they find out there really are a lot of steps involved in getting a user to the real value state. Great things just building this list calls out are a) the things that happen outside your product (e.g. meetings) and b) other players in the decision process (e.g. boss, CFO, partner). You should think of it as a superset of your conversion funnel, and put numbers against the steps that you can. Now, which steps (I like to choose two to three) are your main issues to focus on for the next 90 days?

Some of the questions that come up in this exercise

Each of these steps, actions, will also have an associated motivation (why they took that action) and expected reward (what they ideally hope to achieve by taking that step). Action + motivation + expected reward is, essentially, a behaviour. Understanding complete behaviours will give you a rich set of options of how to encourage users to perform the desired action. For example, you can appeal to emotional rewards, or confirm motivations by comparing the step you want them to take with something they do already. I like to point out the Transferwise example here, where at one stage of the journey the customer needs to go off-site (to their bank) to initiate the transfer. Completely lacking in visibility here, Transferwise instead appealed to the emotional reward with a “One more step and you will have avoided massive fees!” type statement.

I’ve written a bit on how to then turn these into actionable initiatives in my Backlog article.

Your now-better-aligned team should come up with lots of ideas here, and many of them will not be product solutions, which is great! Several times, for example, the teams I work with have come up with sending gifts, like chocolates, to the person they wanted to use the product “one more time”, but it could equally be helpful to simply reposition the step by promoting the respect your user would achieve from colleagues by using a new exciting product.

By now you’ve built your Customer Journey, you are thinking from the Customer’s point of view, you have identified key behaviours that you need to focus on, and brainstormed different ways to encourage your customer to perform these key actions that make your business work. There is a ton more you can do with your Customer Journey (thus my opening statement), but for now I’ll leave you with just a few extra-credit ideas;

This is an update to a previous post entitled Behavioural Roadmap which is no longer live.

For a list of all my articles: https://seedcamp.com/eir-product-articles/

This article was written by Taylor Wescoatt, one of Seedcamp’s Experts-in-Residence. Follow Taylor on Twitter @twescoatt.

“I have the vision in my head, but I don’t know how to get it into the heads of my growing team so they can execute what and how I want them to” — Startup Founder

I have heard this a lot (spoken or unspoken) in startups. It stresses out the Founder, it frustrates the new marketing or UX person who wants to show they can make a difference, but aren’t quite sure how to.

Rallying around a five-year Vision Statement is fine, but what exactly should your team be doing TODAY to make that come true? I like to use a breakdown of the Five Year Vision I call “The Vision Roadmap” that I started developing at eBay and found well received later at Time Out and Emoov. By expressing your Vision in progressive steps, by customer segment, in the customer’s own language, you can;

Make the Vision Actionable

“Who Are We?” – good question, but you need to answer it on many levels. Answer this for each of your customer segments (e.g. early adopters, followers, and service providers or suppliers), and identify how this changes over time. Collectively, and cumulatively, these eventually lead to the full realisation of your Five Year Vision.

The goal of this format is to allow you to render the roadmap between now and fully realising your vision. You recognise that your business will transform in stages over time, and this helps you focus on achieving those stages.

“This works nicely in an agile world where the lighthouse stays the same, but the tactics evolve as we build, test, and iterate toward the vision” — Bill Watt, Product Director, GoDaddy

The CarSparkle Vision Roadmap

So, for example, let’s say you’re building a mobile app for at-home car-washes & services, “CarSparkle”, and your Vision is “Car washing, servicing, and overall management all from your phone”

Each entry is called a User Proposition, that is, what you mean to them. How does this help?

“I liked the proposition approach to (1) diverge vision from product development, and an evolving sales strategy, and (2) a way to manage customers’ expectations” — Didier Vermeiren, Founder, Rial.to

This doesn’t take long to do. You and your Co-Founder can rip it out in an hour or so. If it takes longer than that, all the better because you’ve identified what must be a serious hurdle in realising your Vision. Your team will thank you as they dive back into work re-energised with a clearer sense of purpose and strong connection to the Vision. Follow it up by asking them to give you a revised execution plan. Drop it into your deck, it will be a nice touch to drive that next investor meeting in the right direction.

Once you have this sorted out – you may want to move on to the Customer Journey.

This is an updated version of an older post which is no longer live.

For a list of all my articles: https://seedcamp.com/eir-product-articles/

This article is written by Taylor Wescoatt, Expert in Residence at Seedcamp. Taylor’s background spans 20 years of Product and UX having held key positions at successful startups like Seatwave and CitySearch, and larger brands like eBay and Time Out. This is the accompanying summary of two articles on Roadmaps for Startups; The Vision Roadmap for Startups, and The Behavioural Roadmap for Startups.

Congratulations! You’re starting a business, you’ve got a great vision, and a bit of traction. You’re growing, there are a million things to do. How do you decide what to focus on first? Everyone’s asking for different things. You need a Roadmap.

Typically Roadmaps are typically gantt-chart style diagrams of ‘what we’re going to build’. I’ve put together a lot of these “Feature-led Roadmaps”, and while the final product of long labour is usually appreciated, its pretty much out of date the moment it’s printed. This is confusing for everyone. Features are simply an abstraction between the Business and the needs of your User.

In this series I share a model of roadmapping for Startups specifically. The goal is to get everyone aligned on what is being built and why.

We begin with translating your Vision into a Vision Roadmap full of staged Propositions, or ‘how a segment sees your brand at a given time’.

Each Proposition can then be translated into a full User Journey of Behaviours necessary to achieve that Proposition. Focusing on key Behaviours and only then starting to brainstorm features leads to a far more aligned, well thought through, and persistent plan that a startup can go build Minimum Viable Product tests against in order to validate your thinking and drive your business forward.

If you use these techniques, you’ll find as most startups do that you’ve got a renewed, refined, more accessible plan for delivering your vision.

Good luck!

Copyright © 2019 Seedcamp

Website design × Point Studio